I have been traveling recently and I was able to spend a long time walking in Japanese Forests. In Japan this is known as Forest Bathing which is great for the mind and it gave me time to think. As a result, I have been inspired to attack a slightly more philosophical question this week surrounding AI and copyright. Please indulge this philosophical detour as I believe that the outcome is vitally important to the future of AI Development. Before I do that, let’s look at Robot Scientists and Dinosaurs and the hunt for Ancient Etchings in Peru.

Robot Scientists

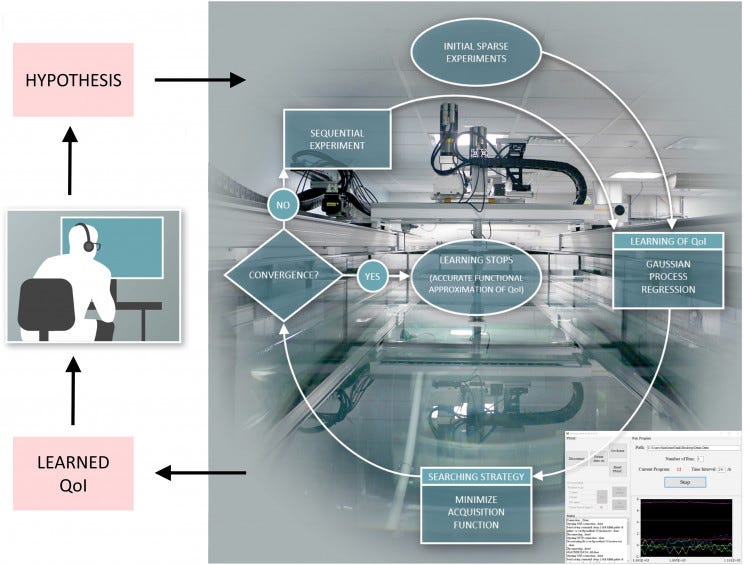

Researchers from MIT and Brown University in the U.S., and the École Normale Supérieure de Rennes in Bruz, France have developed a robot that was able to carry out 100,000 experiments in a year. The "Intelligent Towing Tank" was developed to test out hypotheses in Fluid Dynamics. This about the same number of experiments in Fluid Dynamics in all the years prior to the development of the robot. This complex field is difficult to study and the massive number of experiments carried out automatically allows a wider range of parameters to be tested. Every two weeks the robot completed the same number of experiments that the average Phd student completes.

The system will allow more complex research questions to be answered. So far, these types of questions have been too impractical for humans to research alone. There are other robot scientists in Chemistry, Genomics and drug testing. DARPA has an AI that will read 10’s of thousands of research papers to develop alternative potential hypotheses. Robots won’t replace scientists but they will allow a much wider range of experimentation in a shorter time period. This should hugely assist scientists to make breakthroughs more quickly and more cost effectively.

Robot Hotel Staff

During my recent travels I stayed in a hotel in Osaka that had Robot Dinosaurs as the checkin staff. The Hotel was newly built this year so my hopes for a meaningful interaction with a robot dinosaur were high.

Unfortunately, I was extremely disappointed. The robots move up and down a little and respond to any word said in Japanese or English with a prerecorded instruction to checkin via the self service kiosk next to the desk. They did not respond to Mandarin or any European languages. There was no understanding of what was said (plenty of chatbots can understand the basics) and no sense of interactivity. If these robot dinosaurs don’t improve their performance dramatically they will certainly go the way of their carbon based cousins.

AI and the hunt for Ancient Etchings in Peru

In the Nazca Desert in southern Peru, there are giant etchings that only make sense from a great height. They were first discovered in the 1920’s and were created between 200BCE and 600CE. The etchings were created by removing stones to reveal the sand beneath. They depict geometric shapes, people and animals and are known as Geoglyphs.

Over the past 15 years Japanese researchers have uncovered 142 new designs. The Geoglyphs fall into two main categories, larger animal-like designs (up to 100 meters long) and smaller symbols (some less than 5 meters). There are many more etchings waiting to be discovered however the passage of time has caused the etchings to be damaged by floods, road development and urban expansion. This is where AI comes in. IBM has developed a deep learning algorithm to help speed up the hunt. Stitching together geospatial data, lidar, satellite and drone images and geographical surveys, high fidelity maps of potential search areas are created. The AI is trained to recognize data patterns of known lines to look for new ones. During testing new humanoid images that had previously been missed were discovered. The discovery took only 2 months, previous methods had typically taken years.

If an infinite number of monkeys can type Hamlet, what can an infinite AI type?

There is an old mathematical theorem that if you sat an infinite number of monkeys, each in front a typewriter and they all randomly hit keys, one of them would “almost surely” type the entire play, Hamlet. This theorem was usually used to describe the difference between possibility and probability in maths. “almost surely” is a mathematical term meaning the probability of an event happening is 1 (or 100% chance). Variants on the theorem have been used since Aristotle, up to and including the Simpsons (although Mr Burns only had 1,000 monkeys, it was enough to impress Homer).

In the age of AI we might encounter a practical application of this theorem. There is the potential for real world implications. If we have enough AI computing power then an AI could write any combination of numbers and letters to create every possible combination including Hamlet. The question then becomes, could the AI copyright every single combination of letters and numbers and then charge for use of these works? This might seem a bit far fetched, however there are significant implications in relationship to the ownership of AI created works.

AI created Works and Copyright

When computers first started “creating”, it was clear that the computer was merely a tool for a human creator to develop a work (writing, art etc.). However as AI has developed we are now starting to see AI created works. Paintings, songs, software and a range of other “works”. Some of these works will have value, so who owns the copyright?

Takashi Yamamoto, a Japanese Technology Lawyer has written a paper outlining the issues involved with copyright ownership and AI. Unsurprisingly, the law varies in different countries. In Japan and Germany there is no protection, in the UK the person for whom the work was created (i.e. the customer or owner of the AI) is deemed to be the copyright holder and thus the work is protected. In the US it is unclear however the US Copyright Office has declared that AI works can not be registered.

The question of should AI works be copyrightable is complex. It depends upon the intent of the law. For example under the US Constitution the purpose of copyright is not to protect labor or personality of authors, but to promote the progress of science and useful arts. The intention is to motivate creators to create. In this scenario copyright might be applicable. Yamamoto goes through a range of arguments including what might happen to the market if there is copyright or no copyright for works. This is an economic argument that proposes that copyright protection (vested in the owners of the AI) will balance the supply and demand and thus the incentives for creation of AI works. If there is no copyright and thus no incentive to create, either by AI or humans, this usually leads to a market failure.

It seems to me, that the question therefor is what protection should AI works be given and for how long. I will let the lawyers and economists debate the merits of the mechanics of these issues. However if there is no value that can be protected for AI created works, writing, designs, drugs, paintings, systems, software, algorithms and other beneficial products then all the money being invested in developing AI systems to create these works will be wasted. If it becomes clear that AI created works can not be protected, the investment and thus the development will drop to zero very quickly. This will be a massive limitation to our progress.

Finally if a banana taped to a wall is worth US$120,000, my computer’s musings should be able to be worth something. The market should decide what they are worth.

Paying it Forward

If you have a start-up or know of a start-up that has a product ready for market please let me know. I would be happy to have a look and feature the startup in this newsletter. Also if any startups need introductions please get in touch and I will help where I can.

If you have any questions or comments please email me via my website craigcarlyon.com

I would also appreciate it if you could forward this newsletter to anyone that you think might be interested.

Till next week.